Financial Markets

Stocks, as measured by the S&P 500 Index, gave up ground in the third quarter, but still sport double-digit gains year-to-date. Despite their decline, US large capitalization stocks continue to lead most primary stock indices around the globe in 2023. The S&P 500 was down only 3.3% during the quarter, while the Russell 2000® Small Cap Index lost 5.1% and the MSCI World ex-US (developed market) Index fell by 4.1%.

Interest rates rose during the quarter, leading bond prices to decline. Rate increases were most pronounced at longer maturities; the yield on the bellwether 10-year US Treasury increased by 0.78 percentage points and ended the quarter at 4.59%, near its highest level since 2007. With both stock and bond prices down for the quarter, the relationship between the asset classes continues to show a positive correlation – as it has for much of the post-Covid era – with inflation and interest rates affecting them in similar ways.

Equity sectors that have historically been sensitive to changing interest rates exhibited such behavior in the third quarter; utilities and real estate stocks were the worst-performing sectors. Conversely, energy stocks rose sharply as oil prices jumped on supply concerns.

Investment Perspectives

As we enter the year’s final quarter, it is apparent that the economy has fared better in 2023 than many investors predicted. A year ago, generationally high inflation figures were top-of-mind, leading to fears that the requisite policy response would send the economy into recession. Since then, price increases have slowed while economic activity has remained resilient. Expectations for future inflation have also declined. But despite the considerable progress, price trends in certain key areas remain elevated, and the economy is not yet in the clear.

Price Inflation: Down but Not Out

The most recent Consumer Price Index report indicated inflation is still elevated at 3.7% but getting closer to the Fed’s 2% target. The prices of many types of physical goods have either stabilized or declined. Energy prices, including gasoline and natural gas utility services and the underlying commodities, have fallen over the past year. Prices on items such as vehicles and apparel have continued to rise, but at a slower pace as supply chain pressures eased and consumers shifted spending patterns back toward services. But the result of more services spending has been continued price increases in this area, which includes everything from personal care to recreation. Importantly, housing costs — which account for over half of the services spending basket — have remained elevated, with shelter inflation now at 7.3% over the past 12 months.

As we have stated previously, it takes time for a slowdown in the rise of housing costs to manifest in the data. For instance, in the rental market, changing market prices can most readily be observed in newly signed leases; existing tenants tend to get smaller price increases, though they experience them for longer as their rents catch up with the market price. Aggregate inflation readings include both tenant types, so the lag in rental price changes can be pronounced. A similar phenomenon occurs as the statisticians attempt to find the “owner equivalent rent” — a data point achieved through surveys in which homeowners estimate the cost they would incur if they were renting their homes. This estimate is dependent on owners’ local market knowledge and informed by recent transactions, which again tend to lag the actual market for rental homes. We expect these lagged increases to continue in both measures of housing costs before eventually moderating in the coming quarters.

Wage Inflation: Nearing a Peak?

The labor market has maintained its momentum. The unemployment rate remains near its lows while the rate of wage increases has stayed elevated. Other signs of labor market strength include the recent spate of high-profile union contract negotiations in the entertainment, logistics, and auto industries. However, some data underscoring a robust job market could ironically portend future weakening. For instance, the participation rate — the number of those either employed or seeking employment as a percentage of working-age adults — continues to move higher toward pre-pandemic levels. On its face, this indicates labor strength: workers are enjoying rising wages and their pick of the litter when it comes to job openings. But it may also be a sign that more people are compelled to work again after their stimulus money has run out and student loan bills resume. Add in that job openings have fallen from their highs at the beginning of the year, and it is evident that the balance between supply and demand in the labor market is beginning to shift. Eventually, this could manifest in slower wage gains and increases in unemployment.

Lagged Effects of Higher Interest Rates

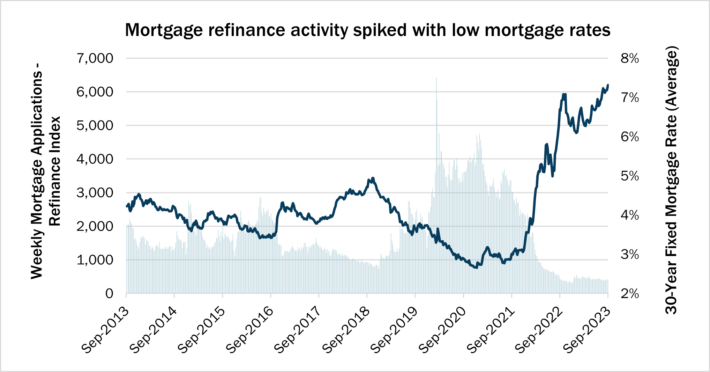

The Fed began raising interest rates in March 2022 and is now likely near—if not already at—its peak rate. But the full effects of these interest rate hikes are not immediate, and in the quarters ahead, we expect to see more of their reverberations throughout the economy. One example of such a lag is evident in the housing market. To be sure, mortgage rates have moved considerably higher since the Fed began raising interest rates. For some mortgage structures, rates are at levels not seen in a quarter century and are surely part of why mortgage demand has largely flatlined. However, home sale prices have yet to materially slow their ascent. Much of this relates to the chapter we just closed — namely, one of historically low interest rates in which homeowners clamored to refinance existing mortgages and lock in such rates. The chart shows the extent of such refinancing activity in the last several years and how quickly it came to an end as rates jumped.

With such attractive financing secured, many would-be sellers are reticent to move given the higher interest rates they would be paying on their prospective home mortgages. Indeed, existing home sales transactions have fallen in 16 of the past 18 months as the supply of homes on the market declined. Activity relating to housing permits, starts, and new home sales has fared better, but the limited existing housing supply has provided a floor to home prices even as affordability wanes with the higher interest rates. Like the rental market, we expect this to normalize in time as variable-rate mortgages eventually reset higher and life events requiring a change in dwelling reduce the friction in the housing market.

Beyond the ramifications of rising financing costs on the housing market, there is a similar effect to be seen in the world of corporate financing. Like homebuyers with mortgages, corporate bond issuers took advantage of ultra-low rates to finance business expansions and enhance shareholder capital returns (e.g., share buybacks). However, as those issuances come due, they will be refinanced at higher rates — with increased interest expense weighing on future profits. This, of course, is part and parcel of why we seek to invest in companies with sustainable balance sheets — those that are not overextended in debt markets and can weather such a change in the rate environment.

Outlook and Positioning

The consistent theme among the above dynamics is that there is still plenty to play out as the economy normalizes and absorbs the impacts of higher interest rates. The Fed also appreciates this and has embraced a “wait-and-see” phase of its tightening cycle. Chairman Jerome Powell continues to preach the monetary body’s data-driven modus operandi and has repeatedly reiterated its long-term 2% inflation target. We expect inflation to continue to moderate and for higher interest rates to eventually further slow economic activity. However, the Fed’s recognition of the lag in their bite may serve to prevent overtightening monetary policy and allow the economy to avoid recession, i.e., to achieve the proverbial soft landing.

Aside from the impacts of higher interest rates, we continue to monitor several other risks that could derail the economy’s growth trajectory. The aforementioned labor strikes have the potential to disrupt output materially. In particular, a prolonged strike by autoworkers is likely to be observable in the economic data; automakers and their suppliers continue to comprise the largest manufacturing sector in the US economy. Dysfunction in Washington continues to threaten the economy. In a surprising last-minute resolution, Congress staved off a government shutdown by extending funding until mid-November. Though a potential shutdown may not directly impact economic output, especially if the episode is short-lived, such political skirmishes can have second-order consequences, namely undermining consumer and business confidence and thus spending. Other reckless political activity globally, whether Russia’s continued invasion of Ukraine or China’s posturing toward Taiwan or global trade generally, also offers the potential for significant economic disruption. A litany of other latent risks are present as well: student loan debt continues to rise as required interest payments have been reinstated; consumer credit balances are at all-time highs in the face of rising financing costs; and the broader commercial real estate market is confronting the dual threats of higher interest rates and changing office space requirements in a post-pandemic world. Collectively, these concerns serve to temper our economic optimism.

We continue to invest in quality businesses that we believe have a greater chance of successfully navigating the remaining inflationary pressures as well as the potential of cooling economic demand. Stocks of such companies, provided they are trading at prices that imply realistic growth prospects, continue to offer compelling expected returns for the long term.

With the changing interest rate and inflation environment, bonds have become more attractive investments. In fact, the “real yield” on the 10-year Treasury (i.e., the yield after subtracting the expected inflation rate) is the highest it has been since the Great Financial Crisis. Such high quality bonds can now provide a material return to multi-asset portfolios while also offering a measure of protection in the event of severe economic disruption.